On 3 April, the Academic Library of Tallinn University hosted the official launch of the major bibliographical reference work Foreign-Language Book and Estonica in Estonia, 1494–1830. This three-volume publication is the result of nearly five decades of work within Estonia’s retrospective national bibliography programme, which began back in 1978, at the height of the Brezhnev era.

The programme emerged from a strong desire to preserve and systematically document Estonia’s cultural heritage at a time when national identity faced growing pressure. Its goal was to chart, in a methodical and scholarly fashion, all printed matter published in or relating to Estonia from the dawn of printing onwards. Particularly notable was the bold decision—given the ideological climate of the time—to include foreign-language publications issued in Estonia. These had often been ignored or silenced under official Soviet historiography. As such, compiling this part of the bibliography proved especially challenging and time-consuming, and its release has been awaited for decades.

That wait is now over. Foreign-Language Books and Estonica in Estonia, 1494–1830 provides a comprehensive overview of works published in foreign languages by authors living in Estonia, as well as key texts about Estonia published abroad during the period in question. The bibliography does not include Russian-language materials, which have been handled in a separate project.

Three volumes, thousands of entries

The first volume covers the period up to 1710—when printed matter first reached the Estonian lands via Livonia, and when the earliest printing houses were established in Tartu, Tallinn, and Narva. It includes works by local authors that found their way to European universities, as well as publications related to the Livonian War and its aftermath.

The second volume spans the years 1711 to 1830—a period of gradual intellectual recovery in the wake of the Great Northern War. In the latter half of the 18th century, printing activity intensified: weekly newspapers began to appear, followed by the first periodicals. Enlightenment ideas were introduced to the region by scholars who had resettled here from Germany; in their writings, they explored local conditions, reflected on the lives of Estonian peasants, and occasionally criticised serfdom. The reopening of the University of Tartu in the 1790s ushered in a new era of scholarly publishing and deeper academic engagement with Estonia’s history and natural environment.

The third volume consists of extensive and detailed indexes—by personal name, title, institution, subject, language, and place of publication. In many cases, short biographical notes are provided, complete with references. The bibliography includes over 8,400 entries in a wide range of languages, including German, Latin, Swedish, French, Polish, Hebrew, Greek, English, Latvian, and Czech. The publications represented are equally varied: books, pamphlets, music booklets, calendars, broadsheets, atlases, and almanacs.

A cornerstone of cultural memory

The work was compiled by bibliographers Helje-Laine Kannik, Kertu Maasik, Tiiu Reimo and Aira Võsa, whose decades of dedicated scholarship represent a truly remarkable contribution to Estonian cultural history. The volumes were published by Tallinn University Press in the series Acta Universitatis Tallinnensis. Humaniora, with support from the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, the Ministry of Education and Research, and the National Culture Foundation.

Although a valuable resource for librarians and researchers, this bibliography is by no means limited to specialists. It offers rich material for anyone interested in Estonian heritage, early modern intellectual history, or the broader cultural currents of Europe.

The translator and Estophile Cornelius Hasselblatt has described the bibliography as a walk through Estonian history—an exploration that reveals forgotten works, unexpected cultural intersections, and overlooked gems. In his words:

“What better way to illustrate and embody Estonia’s interwoven cultural history than by listing the publications printed here and those published elsewhere about this land? These works are not only significant from the perspective of Estonian cultural history—they are part of Europe’s intellectual and cultural heritage. That is why this bibliography is a vital tool for researchers in multiple fields, and it deserves a place in every serious academic library.”

This is a scholarly achievement of rare scope and depth—the kind of publication that appears perhaps once in a century.

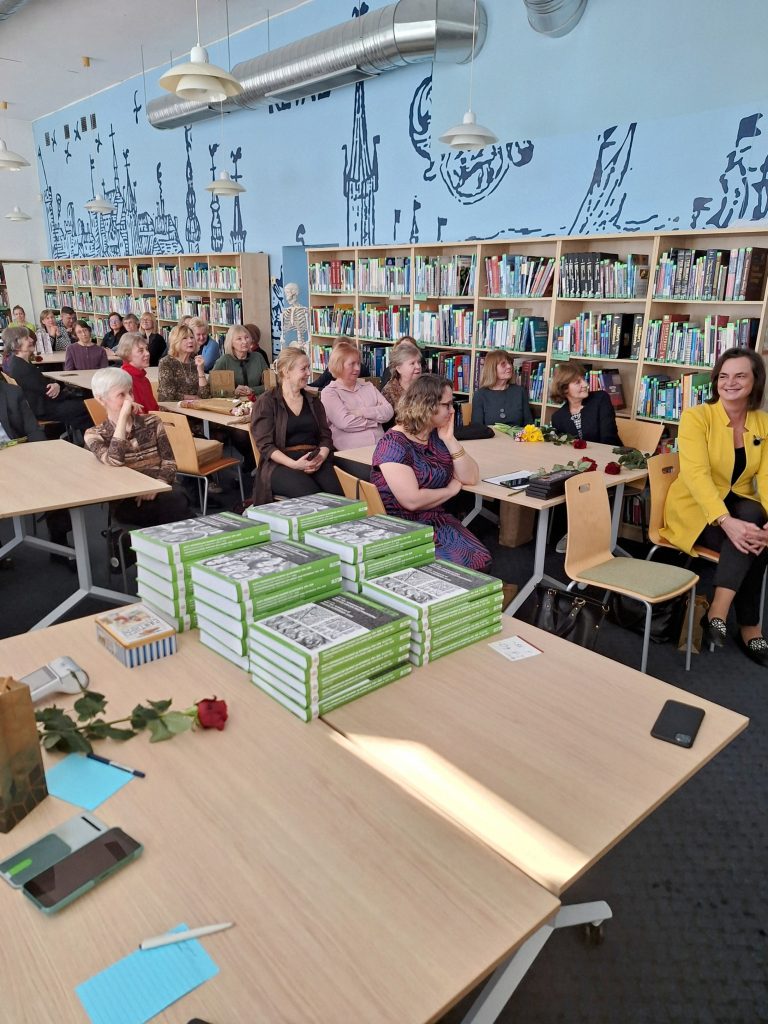

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the making of this remarkable work and joined us in celebrating its launch. Here is a small selection of moments from the presentation day: