The Institutiones Iustiniani, or Justinian’s Institutes, forms part of the Corpus iuris civilis (“Body of Civil Law”), which was compiled between 529 and 534. The title Institutiones cum glossa (ordinaria Accursii Florentini) indicates that this edition includes explanations, marginal notes, and commentaries on the texts – in other words, it is an annotated edition. According to some sources, the commentator is identified in the title as Franciscus Accursius the Elder (c.1182–c.1260). In any case, Accursius’ name appears consistently throughout the commentary text.

Justinian I (Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus Augustus), known as Justinian the Great (c. 482/483 – 14 November 565), was Emperor of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire from 1 April 527 to 14 November 565 – a reign of 38 years, 7 months, and 13 days.

Justinian I’s primary objective was to restore the Roman Empire, the western part of which had fallen in 476. He sought to reconquer these Western Roman territories from the Frankish and Germanic tribes. His notable achievements include the conquest of North Africa in 533, the conquest of Italy between 535 and 540, and the compilation of Roman law known as the Corpus iuris civilis between 529 and 534. During his reign, Byzantine culture flourished, and the Hagia Sophia cathedral was constructed. In the Orthodox Church, he is venerated as Saint Justinian the Emperor.

Justinian’s greatest legacy was the codification of Roman law. He wanted the Eastern Roman legal system to match or surpass that of the West. Inspired by the Western Roman legal tradition, he commissioned the creation of a comprehensive legal system for the Eastern Empire, which became the Corpus iuris civilis.

The Corpus iuris civilis is a collection of Roman law commissioned by Emperor Justinian I in 528 and completed in 534. Although often referred to as the “Code of Justinian”, this name strictly applies only to the first part, the Codex. The Corpus iuris civilis was written and circulated almost entirely in Latin, which was the official language of the empire, even though Greek was the predominant language spoken in the East. This language barrier hindered the general public’s understanding of the new legal system and was a primary reason why interest in legal literacy did not take root.

The term Corpus iuris civilis was adopted in 1583. The codification of Roman law that came to be known by this name in the 16th century remains a principal source of Roman law to this day.

ustinian’s Corpus iuris civilis originally consisted of three, and later four, separate parts: the Codex, the Digesta or Pandectae, the Institutiones, and the Novellae. The Codex and Digesta were the most important parts of Justinian’s compilation, but they were too complex for law students of the time. Therefore, Justinian ordered the creation of an instructional text, the Institutiones. This was modelled on the Institutiones of Gaius, composed four centuries earlier. The Institutiones served as a supplementary part of the Codex, offering educational material and supporting the other sections of the code. Although it was designed for educational purposes, the Institutiones held equal legal weight with the Codex and the Digesta. The Institutes were a concise textbook of civil law and held the force of law. For centuries, the Institutiones served as the textbook for first-year law students.

Unlike the other parts, the Institutiones did not cite the origin of its sources; it was written as a coherent and unified text adapted by its authors to reflect the laws of their time. Justinian’s Institutiones are divided into three main categories: actions, persons, and things. The text is divided into four books, each of which is further subdivided into titles with appropriate headings. Later, these titles were divided into paragraphs.

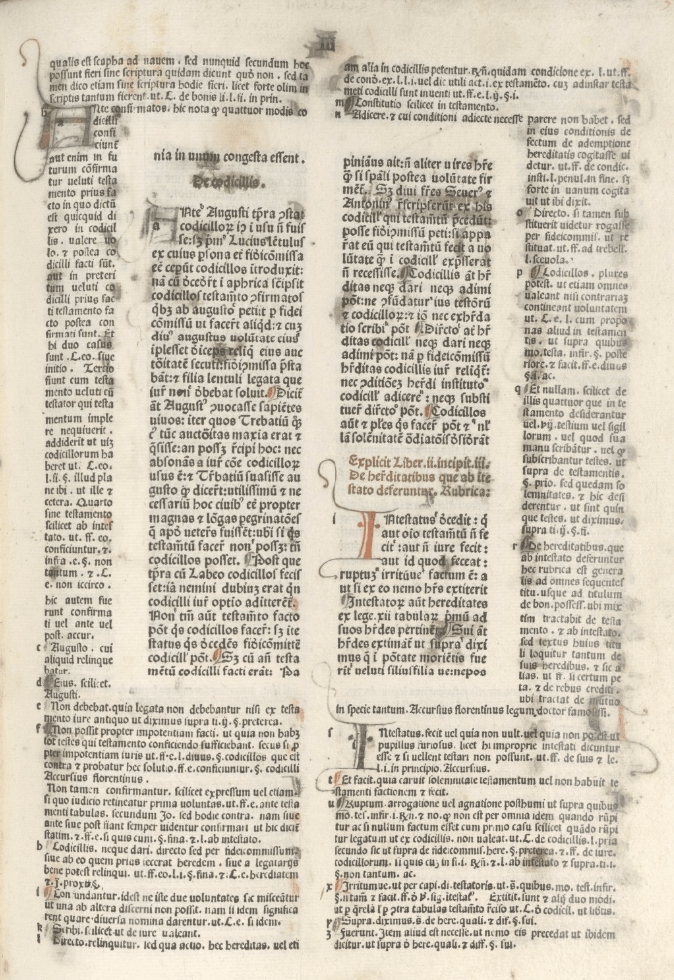

The incunabulum Institutiones cum glossa was printed in Venice on 20 July 1478 by Jacobus Rubeus. It is hand-illuminated with red and green initials and includes rubrication in two colours. The text is printed in red and black, and the layout clearly distinguishes the main body of the Institutiones, which occupies the centre of each page, from the surrounding commentaries. This type of layout is quite common in early printed books. The book originally belonged to the Franciscan monastery in Rakvere, first mentioned in sources in 1472. The monastery burned down in 1526. It was later rebuilt and dedicated to the Archangel Michael – hence the later name, the Monastery of St Michael in Rakvere. However, during the Livonian War in 1558, it was completely destroyed by the Russians. In 1564, the remaining assets were distributed – some were given to Narva, others to St Nicholas’ Church in Tallinn. The book then came into the possession of the Library of St Olaf’s Church in Tallinn, and in the 19th century, it was part of the Estonian General Public Library. From there, via the Estonian Literary Society’s library, it eventually came into the collection of the Department of Preservation of Baltic and Rare Books at the Academic Library of Tallinn University. The connection to the Rakvere monastery has been confirmed by the earliest inventory of the St Olaf’s Library, where this and other printed works are marked with the note “E bibliotheca Wesenbergensi a. 1564”, in which the year presumably indicates when the books arrived from Rakvere to the Tallinn library.

The incunabulum is bound in a Gothic-style binding, ornamented with individual stamps. The wooden covers are reinforced with bands and fastened with two brass clasps. The binding is further strengthened by ten large protective nails (which were missing prior to restoration), and the corners are edged with brass angles. Prior to restoration, the leather cover was heavily torn, and the surface had become scaly. The book underwent extensive restoration in 1997, a process documented in the video film The Rebirth of an Incunabulum. During the restoration, the covers were reattached using adhesive and wooden pegs, the leather was repaired and softened, and the missing protective nails were replaced. The paper of the printed book had also become brittle and deteriorated, and it was restored using a paper casting technique.

You can view this incunabulum in ETERA.